.avif)

Rhushik Matroja

CEO

.jpg)

For the first time in decades, the relationship between engineers and their software is being rewritten. AI agents are beginning to automate the repetitive execution work that has consumed engineering hours for a generation, while a new protocol, the MCP (Model Context Protocol), is making it possible to deploy these capabilities on-premises, with deterministic accuracy, inside the most security-conscious organizations on Earth. This article explores what's changing, how it works, and why the engineers who thrive in the next decade will be the ones who learn to steer intelligent systems rather than operate conventional tools.

There is a particular kind of frustration that most mechanical engineers know intimately but rarely articulate. It's not about the physics; the physics is the part they love. It's about everything that surrounds the physics:

Despite two decades of continuous software investment (more powerful solvers, richer CAD kernels, faster meshing algorithms) the fundamental architecture of the mechanical engineering workflow has not changed. It remains sequential, manual at its core, and built around the engineer as an operator of disconnected tools rather than as a decision-maker navigating a design space. The tools have become more capable, certainly, but the workflow they serve was conceived in an era when computation was scarce and human labor was the only available integrator between design steps.

The result is a paradox that engineering leaders increasingly recognize: organizations possess extraordinary engineering talent, invest heavily in software infrastructure, and yet the creative, judgment-intensive work that defines competitive advantage (exploring trade-offs, identifying optimal configurations, making decisions that balance performance against cost and producibility) remains compressed into a fraction of actual engineering time. The rest is tool operation.

What if the tools finally caught up with the engineer's ambition?

The conversation around artificial intelligence in mechanical engineering has been clouded by marketing noise and imprecise terminology. To cut through it: AI's genuine contribution to engineering is not generating prettier shapes or running simulations marginally faster. It changes the relationship between the engineer and the software: creativity is no longer limited to what current tools make practical to execute.

Today, there exists a persistent gap between what a skilled engineer knows should be possible (the concept they can envision, the trade-off they understand intuitively, the optimization pathway they would pursue if time permitted) and what they can actually execute within the constraints of their toolchain. That gap is defined by the software's interface complexity, its learning curve, the rigid sequential logic it imposes, and the sheer manual effort required to translate engineering intent into computational input. AI collapses that gap. An engineer who wants to generate optimized concepts from a set of requirements (load cases, material constraints, functional surfaces that must be preserved) simply describes the intent. The system does the rest: geometry generation, simulation setup, optimization execution, performance validation, report compilation. Not approximately. Not with caveats. End to end.

This is a structural shift, and it manifests in two ways that matter.

In conventional workflows, engineers translate their domain knowledge into software commands: sketching profiles, assigning boundary conditions through dialog boxes, defining mesh parameters, configuring post-processing outputs. Every step requires the engineer to speak the software's language rather than their own. AI inverts this relationship entirely.

The engineer defines what the part must achieve: the performance envelope, the material system, the load scenarios, the functional interfaces that cannot be modified. The system determines how to get there, selecting which operations to sequence, which parameters to set, which solver configurations to apply. The interface becomes a conversation between engineer and system, conducted in the language of engineering intent rather than software procedure.

When multi-step workflows (meshing, FEA simulation, topology optimization, manufacturability assessment, report generation) execute as a continuous autonomous loop, the engineer's role transforms from operator to architect. Fifty optimization iterations in the time previously required for one. The engineer monitors convergence trajectories, interprets trade-off surfaces, and validates outcomes against criteria that require human judgment: is the weight-to-stiffness ratio acceptable for this application? Does the stress distribution align with the expected load path logic? Is this geometry producible at the target cost point? These are the questions that define engineering excellence, and AI finally gives engineers the time and data to answer them properly.

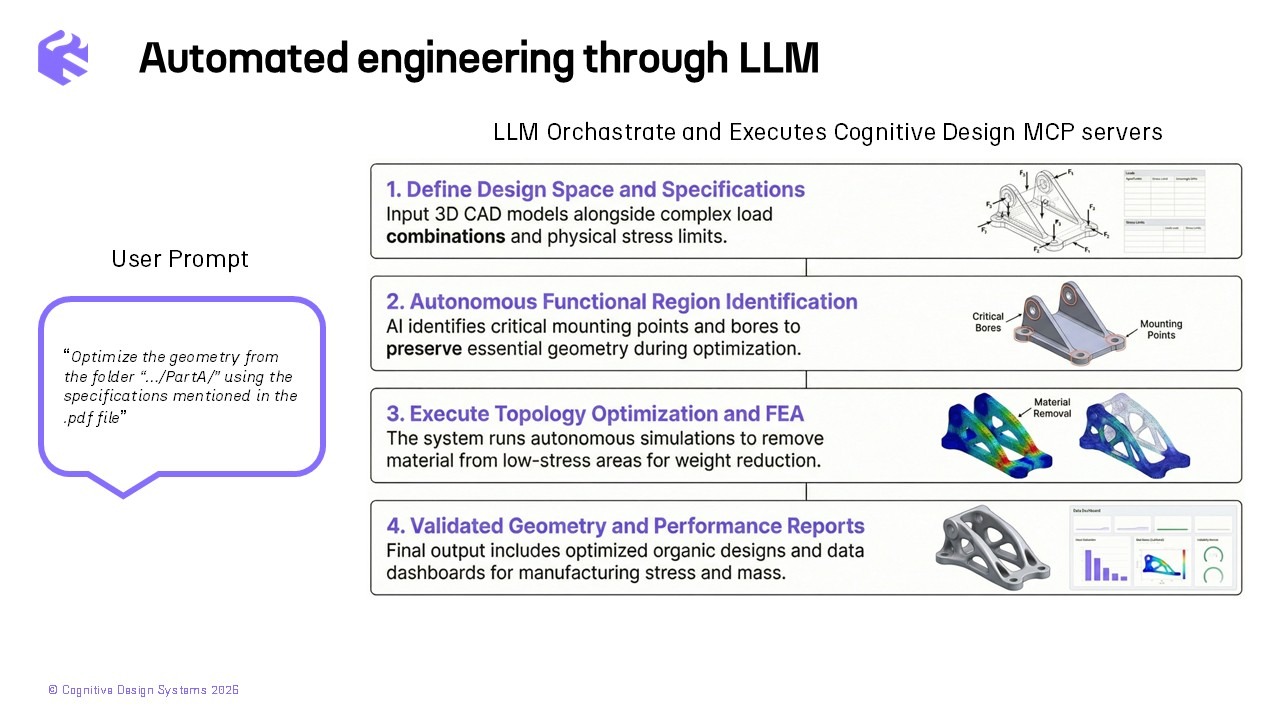

To ground this vision in concrete reality, consider what CDS is actively demonstrating: a fully autonomous part optimization workflow applied to a multi-axis structural component with complex loading conditions and multiple functional interfaces.

The system ingests 3D CAD geometry alongside a matrix of load combinations (forces, moments, safety factors) together with material properties and stress limits. From this input, the AI autonomously performs semantic geometry parsing: distinguishing functional surfaces (central bore, mounting arms, interface planes that must remain exact) from the modifiable design space. This semantic map prevents the system from compromising the component's mechanical utility, the critical safeguard that separates serious engineering AI from generic shape generators.

With functional regions locked, the system enters a closed optimization loop: mesh generation, FEA simulation under the full load set, stress analysis, material removal from low-stress regions, reinforcement of high-stress areas, repeat. This cycle executes autonomously across 50+ iterations, with transparent logging at every step, progressively converging toward geometry that exhibits bone-like structural efficiency where material exists only where forces travel. The output is a manufacturing-ready geometry accompanied by automatically generated dashboards:

A short video demonstrates this AI workflow in action, showing Cognitive Design's MCP server orchestrated by the LLM Claude through a conversational interface. An important clarification: this is R&D work, not the product itself. The demonstration helps our engineering team validate the autonomous workflow architecture and inform the design of our next version of Cognitive Design, but the final product will neither look nor operate like what is shown in the video. It is a research prototype, not a product preview.

The capabilities described above (autonomous workflow orchestration, semantic geometry parsing, closed-loop optimization) require more than a capable AI model. They require a structured interface between the AI's reasoning capabilities and the engineering software's computational kernel. That interface is the MCP.

The MCP (Model Context Protocol) is the standardized layer that connects an AI reasoning engine, the large language model, to external tools and data sources. In the context of engineering, this means connecting the LLM to the CAD/FEA kernel: the computational infrastructure that actually generates geometry, runs simulations, evaluates stress fields, and produces manufacturing assessments. Without this connection, AI remains a conversational assistant that can discuss engineering principles but cannot execute engineering operations. With it, AI becomes an agent, a system that interprets specifications, plans multi-step workflows, and orchestrates computational operations end to end.

CDS has built its MCP server to expose the platform's core capabilities as structured operations that the AI can invoke autonomously:

The engineer interacts through a chat-based environment, directing the workflow using natural language while the MCP translates that intent into precise computational sequences. Every operation is logged. Every decision step is visible. The system provides a transparent record from input specification to final output in deliberate contrast to the opaque algorithmic processes that have historically undermined engineering trust in automated design tools.

For engineering applications, the distinction between probabilistic and deterministic computation is not academic; it is existential. Large language models are, by nature, probabilistic systems: they generate responses based on statistical patterns in training data, which makes them powerful for interpretation, planning, and reasoning but fundamentally unsuitable for tasks where precision and reproducibility are non-negotiable.

Cognitive Design's architecture addresses this directly by coupling the LLM's strengths with deterministic solvers. The AI interprets engineering specifications, identifies functional regions, plans the optimization sequence, and orchestrates the workflow, all tasks that benefit from contextual reasoning and natural language understanding. But every computation that produces a quantitative result (finite element analysis, topology optimization, stress evaluation, mass calculation) runs through validated, deterministic algorithms that yield identical outputs for identical inputs. The results are predictable, reproducible, and fully auditable.

This pairing of probabilistic reasoning with deterministic execution is what makes AI genuinely viable for engineering rather than merely interesting. The LLM contributes what it does best: understanding context, interpreting complex specifications, managing multi-step logic. The physics solvers contribute what they do best: producing exact numerical results that engineers can certify, validate, and defend. Neither capability alone would suffice; combined through MCP, they create something the industry has not had before, an intelligent system that is simultaneously creative in its planning and rigorous in its computation.

For aerospace, defense, and space organizations, the question of where data resides is not a procurement detail; it is a program requirement with legal force. Export-controlled programs governed by ITAR or EAR, classified geometries subject to national security restrictions, and proprietary design logic representing years of competitive investment cannot transit through cloud infrastructure, regardless of vendor assurances about encryption standards or compliance certifications. The risk is structural, not procedural: once sensitive data enters a third-party environment, organizational control over that data becomes a matter of contractual trust rather than physical certainty.

MCP's architecture enables a deployment model that eliminates this concern entirely. The AI agent, the CAD/FEA kernel, and all project data remain on local infrastructure under full organizational control. The practical implications for regulated industries are substantial:

CDS is actively building this next generation of AI-augmented engineering workflows, and we believe the best tools are shaped by the teams who use them. If your organization designs mechanical or thermo-mechanical components and you're interested in exploring what autonomous, physics-driven design exploration could look like inside your workflow, we'd welcome the conversation. We're seeking partners who want to test these capabilities on real components, challenge our assumptions with real constraints, and help us refine an approach that works for serious engineering environments.

Explore our frequently asked questions to understand how our software can benefit you.

Request a demo to see how Cognitive Design by CDS can revolutionize your engineering workflow