.avif)

Rhushik Matroja

CEO

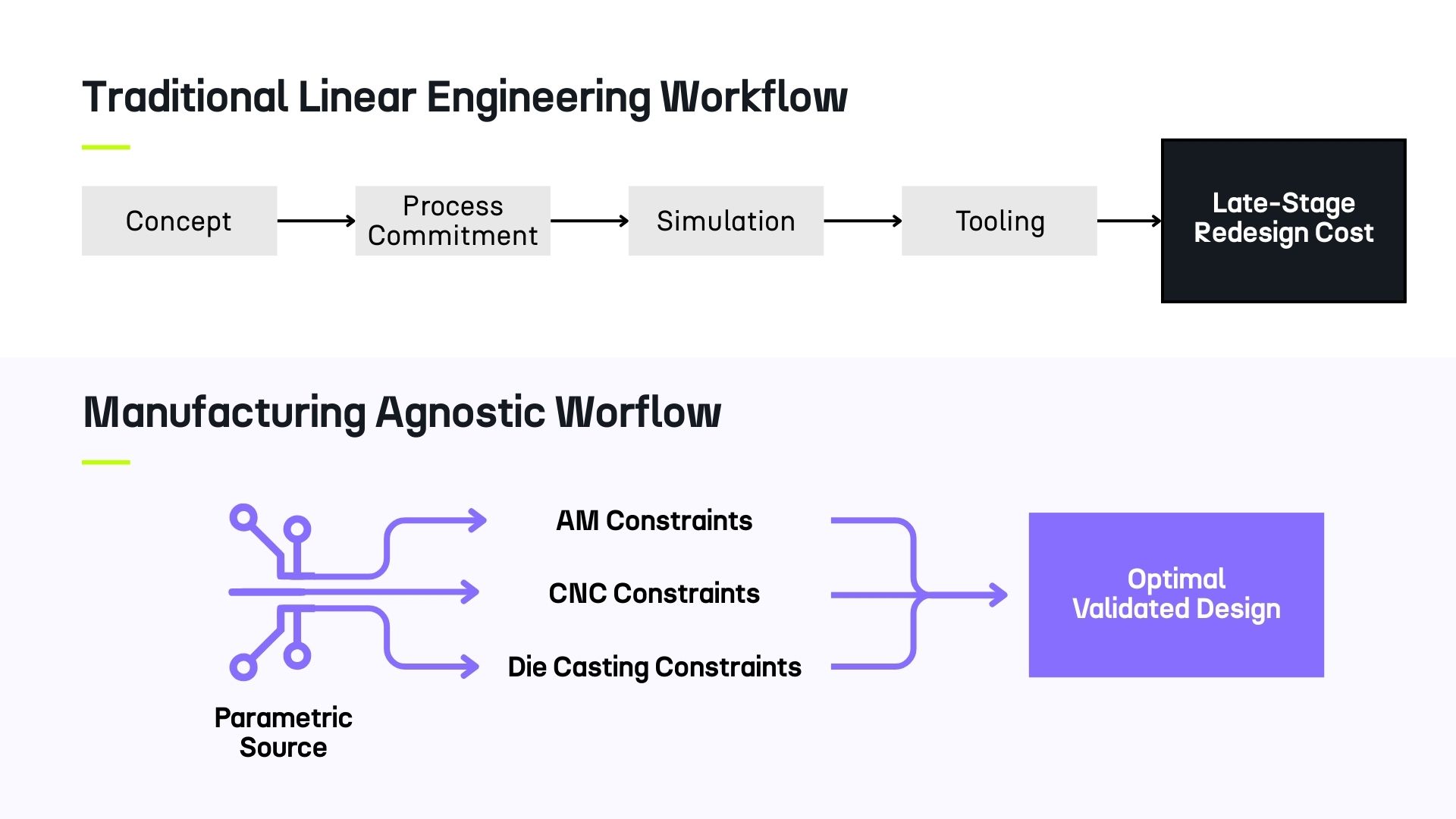

Across mechanical engineering, from aerospace brackets to automotive chassis systems to industrial housings, engineers are routinely forced into a premature commitment to a single manufacturing process long before the optimal design is known. The geometry gets shaped around that choice, simulation validates it, tooling is quoted, and by the time the team discovers a better pathway existed, the cost of switching is prohibitive. This "process-first" bias drives material waste, over-engineered components, and costly late-stage redesigns in every sector where performance and producibility are in tension.

To truly de-risk high-performance engineering, organizations must shift toward Manufacturing-Driven Design (MDD) powered by manufacturing agnosticism: the capability to evaluate multiple processes (such as AM, CNC machining and die casting) in parallel, with process-specific constraints active from the first iteration. In a recent automotive suspension upright case study, this approach achieved a 30% mass reduction while maintaining structural integrity, and engineering lead time collapsed from 96 hours to just 4 hours.

The mechanics of process lock-in are deceptively simple. An engineering team begins concept development and, based on legacy habit, rough volume estimates, or supplier familiarity, selects a manufacturing pathway early in the project. Choose die casting, and you inherit 8-week tooling lead times and geometry constrained by draft angles and split lines. Choose additive manufacturing, and you risk per-unit costs that may never justify the performance gains at production volume. Choose CNC machining, and cycle times and fixture complexity become binding constraints on geometry.

Each of these decisions cascades through the entire development program. The geometry is shaped around a single process. Simulation validates that geometry. Tooling is quoted. Suppliers are engaged. By the time the team discovers that an alternative manufacturing pathway would yield a lighter, cheaper, or more producible component, the cost of switching has become prohibitive.

The fundamental problem is not that engineers choose poorly. It is that they are forced to choose at all before the design space has been adequately explored. In an industry where less than 5% of production volume relies on additive manufacturing, roughly 40% involves precision CNC machining, and approximately 25% of metal components are die cast, optimizing for a single process while ignoring the others leaves enormous value on the table.

The real risk is not selecting the wrong process. It is never knowing what the right answer looks like because the alternatives were never explored with equivalent rigor.

Manufacturing agnosticism is frequently misunderstood as a simple post-hoc comparison: design the part, then estimate what it would cost to produce via different methods. That approach captures none of the value, because the geometry itself has already been optimized for a single set of manufacturing constraints.

True manufacturing agnosticism means something fundamentally different. It is the ability to explore various processes in parallel (additive manufacturing, CNC machining, die casting, injection molding...), with process-specific Design for Manufacturing (DFM) constraints active during the optimization phase itself. The distinction matters enormously. When casting draft angles, machining accessibility zones, and AM overhang limits are embedded into the generative design process from the outset, the resulting geometries are not theoretical concepts that require months of refinement. They are manufacturable candidates, each shaped by the rules of its intended production method.

This parallel, constraint-driven exploration addresses the core equation that governs component engineering: performance is closely tied to design complexity and material properties for each process, while cost depends on material price, production quantity, and manufacturing expenses including pre- and post-processing. Without evaluating these variables across multiple processes simultaneously, engineers cannot make informed decisions. They can only make assumptions.

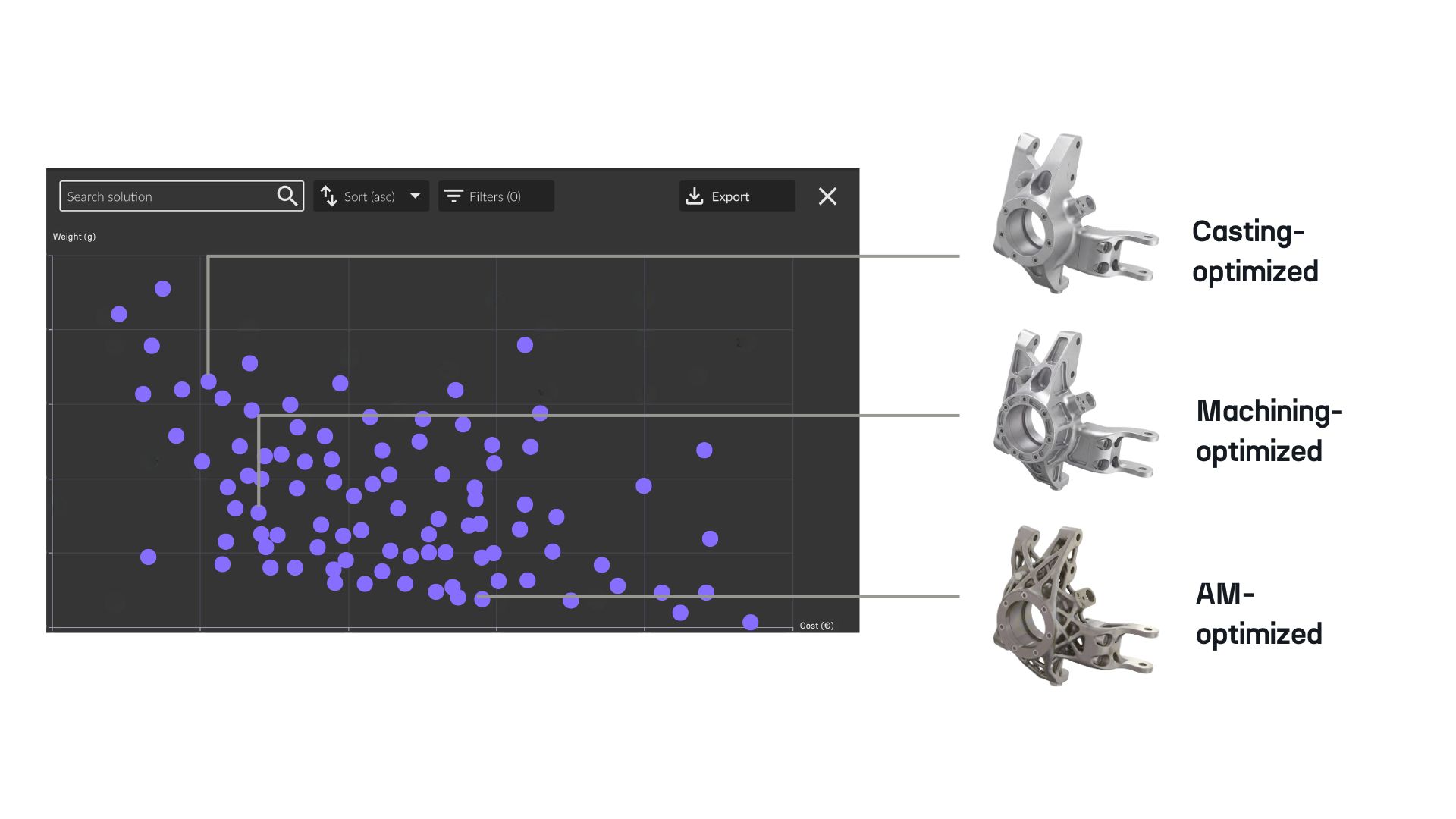

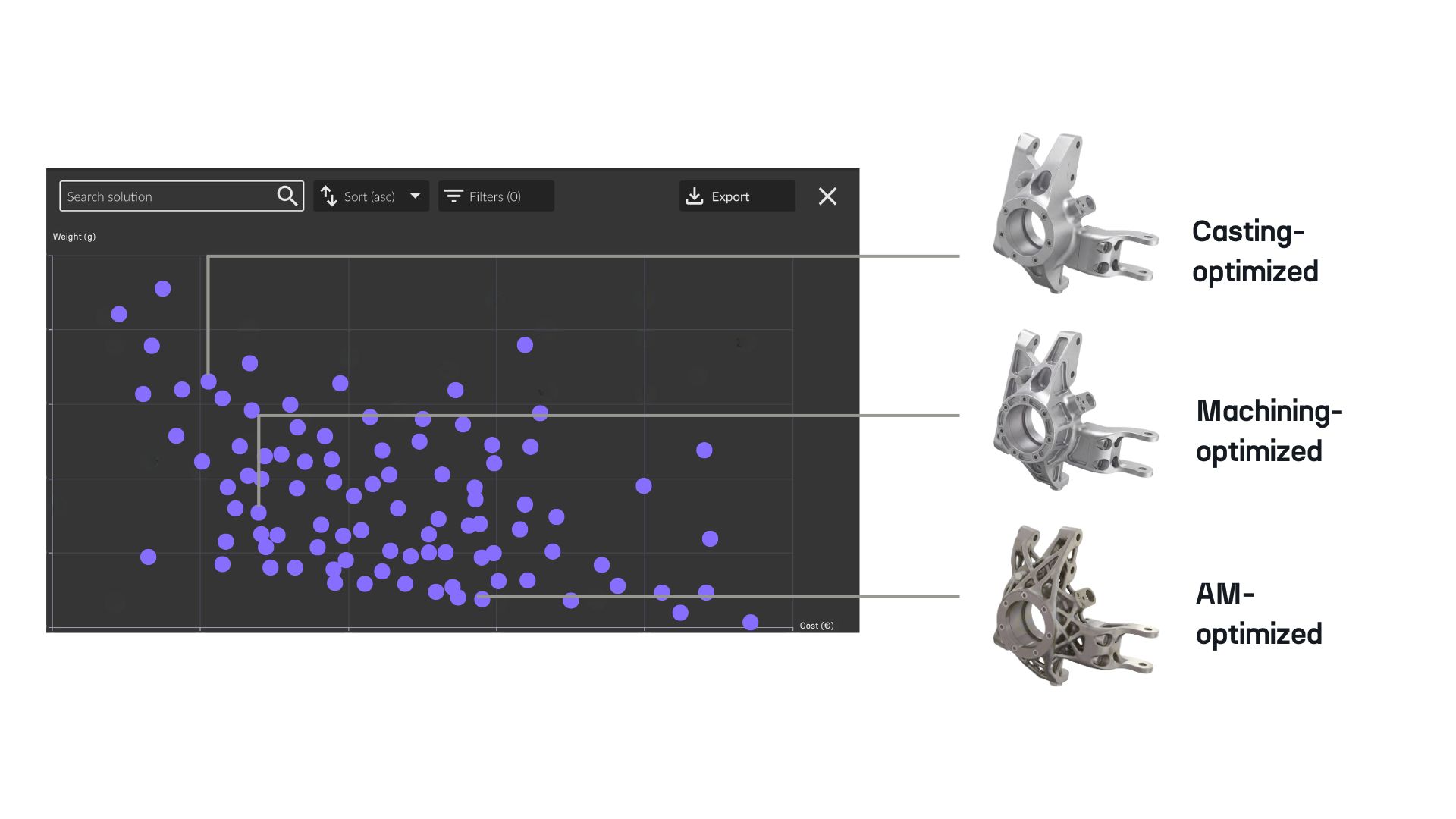

The recent optimization of a high-performance automotive suspension upright demonstrates what becomes possible when manufacturing agnosticism moves from theory to practice. Rather than designing for a single production method and hoping the result would transfer to alternatives, the engineers leveraged Cognitive Design and utilized a Design of Experiments (DoE) workflow to generate over 100 design variations in parallel, each constrained by the rules of its target manufacturing process.

The workflow evaluated three distinct manufacturing pathways simultaneously, with each pathway enforcing its own set of producibility constraints from the first iteration.

The critical insight is that these were not three separate projects. They were three branches of a single parametric workflow, sharing the same load cases (2G braking, 3G vertical bumps), the same packaging constraints, and the same performance targets. The only variable was the manufacturing process and its associated rules.

With all variants generated and automatically evaluated, the engineering team gained access to a transparent matrix of trade-offs that would have been impossible to construct through sequential, single-process iteration.

The titanium AM upright achieved 2.24 kg, delivering 96% of baseline stiffness with organic, stress-optimized geometry. Its estimated production cost, however, reached approximately $850 per unit. The die cast alternative, heavier but dramatically less expensive at roughly $150 per unit, presented a compelling case for volume production where absolute performance is not the sole criterion.

This holistic assessment extends well beyond price and weight. It integrates manufacturability scoring and structural performance validation under critical load cases. Engineers no longer guess at the best outcome. They compare quantified alternatives and select the solution that best aligns with program objectives, whether those priorities emphasize maximum performance, minimum cost, or the fastest path to production.

Perhaps most significant is the collapse of engineering lead time. What traditionally consumed 96 hours of sequential CAD modeling, simulation setup, and manufacturing review was completed in 4 hours within the unified workflow. That is not an incremental improvement. It is a fundamental change in how concept engineering operates.

The automotive upright case illustrates a principle that extends far beyond a single component. Industry consensus, supported by decades of manufacturing research, holds that roughly 70% of a component's manufacturing cost is determined by decisions made during the design phase. Yet in the traditional workflow, manufacturing visibility arrives far too late to influence those decisions without costly rework.

When a topology-optimized bracket achieves theoretical weight savings of 40% but requires five-axis machining operations, specialized fixtures, and triple the cycle time, the business case collapses. When a die cast housing design reaches tooling only to discover that wall thickness variations will cause porosity defects, the redesign cycle consumes four to six weeks and cascades through supplier commitments, certification timelines, and downstream assembly schedules.

Manufacturing-Driven Design eliminates this pattern by embedding producibility analysis into every design iteration from the concept stage. Within Cognitive Design, the workflow follows four integrated stages:

This four-stage loop executes within seconds for each variant, meaning that engineers exploring 60 or more design alternatives receive manufacturability feedback on every single one. The result is that production problems which traditionally surface during tooling or first-article inspection are identified and resolved during the first hours of concept development, when fixes are fast and inexpensive.

Across deployments, this approach has demonstrated up to a 90% reduction in design-manufacturing iterations, translating directly into shorter development timelines, lower prototyping costs, and fewer late-stage engineering changes.

Generating manufacturable design variants is necessary but not sufficient. The second challenge, equally critical, is navigating the resulting design space with confidence and speed.

Traditional concept exploration follows a painful pattern: engineers iterate manually in CAD based on experience, await feedback from simulation teams, incorporate manufacturing constraints reactively, and track results in spreadsheets that grow unwieldy after the fifth or sixth iteration. Under typical program timelines, teams evaluate fewer than five concepts before committing. That is far too few to identify optimal trade-offs across performance, weight, cost, and producibility.

With Cognitive Design, engineers were able to transform this equation through the Design Explorer, an integrated decision-support environment that automatically extracts and compares key performance indicators across every generated variant. The platform evaluates all alternatives across five dimensions simultaneously:

Structural performance including stress distributions, displacement values, and safety factors under defined load cases. Weight with full mass properties and distribution analysis. Manufacturability with process-specific DFM scoring for die casting, CNC machining, injection molding, and additive manufacturing. Cost with estimated production cost by manufacturing process, covering material, machine time, and pre/post-processing. Sustainability with carbon footprint analysis based on material type, quantity, and process parameters.

Rather than reviewing variants in a visual gallery without analytical context, engineers filter, rank, and compare alternatives using quantified metrics. Every variant maintains a traceable link to its input parameters, constraints, and design logic, ensuring that the rationale behind each decision is documented and auditable.

The parametric workflow architecture that underlies this exploration capability provides an additional, often underestimated advantage: when upstream requirements change (a revised load case, updated packaging constraints, or new material selection), the entire workflow recomputes automatically. There is no manual reconstruction, no broken digital continuity, and no weeks of rework to propagate a single change through dozens of variants. Engineers have reported design changes accommodated in minutes rather than days, with workflows generating 60 or more optimized variants from a single parametric definition.

Manufacturing agnosticism and multi-process design exploration are computationally intensive, which is why most commercial platforms rely on cloud-based processing. However, for many of the industries that stand to benefit most from this approach, cloud deployment is simply not viable.

Aerospace and defense contractors handle export-controlled data and classified programs that cannot leave secured networks. Automotive OEMs protect competitive design information with strict data governance policies. Even organizations without formal security requirements increasingly recognize data sovereignty as a strategic concern.

Cognitive Design runs entirely on local infrastructure. No cloud connectivity is required, and no data leaves organizational control. All uploaded geometry, generated designs, simulation results, and workflow definitions remain on local servers or workstations. When collaboration is needed, project files in .cds format package complete workflows for secure sharing between team members or sites without relying on external servers.

This architecture ensures that the full capability of manufacturing-driven design, including parallel multi-process exploration, integrated simulation, and automated DFM analysis, is available to organizations operating under the strictest data governance requirements.

Explore our frequently asked questions to understand how our software can benefit you.

Request a demo to see how Cognitive Design by CDS can revolutionize your engineering workflow